The result of a wish on the part of the local municipality, the Tournai Natural History Museum came into being on 16 July 1828, at a time when the town still formed part of the United Netherlands and during which great progress was being made in the sciences.

Initially housed in the premises of the Town Hall, the first collections were shown to the townspeople for the first time on Sunday 13 September 1829 during the kermesse street party, leading, given that, to the Museum in Tournai becoming the first one in Belgium which the general public could visit.

The Museum was subsequently relocated to its current premises, which are the former location of the Saint Martin’s Abbey brewery. The inauguration took place on 15 September 1839.

Two founders – two great men

Barthélémy Dumortier

Barthélémy Charles Joseph Dumortier, born in Tournai on 3 April 1797, was the initiator of the Tournai Natural History Museum, in 1828. He was to go on to be one of the Museum society’s most active members, even going so far as to spend his own money to enrich the Museum’s collections.

He was – simultaneously – a politician, a learned naturalist and historian. He also created the Botanical Garden of Brussels (in 1866). In Tournai, he set up the “Le Courrier de l’Escaut” newspaper (in 1829), the Royal Agriculture and Horticulture Society (in 1818) and also the Arboriculture (tree-growing) School (in 1861).

Bruno Renard

Bruno Renard, born in Tournai on 30 December 1781, was appointed, on 22 February 1808, as Municipal Architect and as Professor of Architecture at the Académie de Dessin in Tournai.

Despite the fact that today he is most well-known for the main building at Houillères de Hornu and the 200 workers’ houses there (the “Grand Hornu”), in Tournai, he was to be charged by the Town Hall with taking part in all constructional work the completion of which would transform Tournai’s appearance.

It was to Renard that in 1839 the Town entrusted work on internal features of the Museum.

Unique museum architecture

The structure of the gallery and of the square room designed by Bruno Renard in 1839 remains today as it originally was – only the internal presentation of display cases has been changed.

This gallery, which has been conserved in its original state, remains an architectural throwback that is unique in Belgium – and possibly in Europe – to the first “cabinets of curiosities” dating from the 19th century. We consider the gallery to be the first “exhibit” in the collections of the Tournai Natural History Museum.

A rare and prestigious collection

Right from the off and the establishment of the Museum in 1828, Barthélémy Dumortier unceasingly enriched its collections, even spending his own money doing so. In 1839, he managed to gain equal footing for the Museum in Tournai in relation to universities as regards the sharing and the acquisition of collections bought by the government, and in doing so enabled the Museum to obtain extraordinary zoological exhibits:

species that today are rare, endangered or extinct such as, for instance, the thylacine (†) and the passenger pigeon (†) ;

historical exhibits such as the very first elephant in Belgium which underwent taxidermy, which the Museum obtained in 1839 and which is exhibited in the square room.

Amongst the Museum’s most illustrious patrons have been the King of the Netherlands, William I, the King of the Belgians, Leopold I, the Belgian Government and also the Bishop of Tournai, Monsignor Gaspard-Joseph Labis.

A modern museum and a living museum

While, towards the end of the 19th century, the Museum gradually got old-fashioned following the deaths of its founders, and then it had to endure the torments of two world wars, it got back into gear and into form from 1959 onwards, thanks to various projects which were put in place by its successive curators. The Museum managed to move with the times and is today a modern natural history museum, and one which is active in several areas, as follows:

- thus, accompanying the collections of animals which have undergone taxidermy are dioramas (three-dimensional models) which show the animals in their natural contexts ;

- besides permanent exhibitions, each year the Museum puts on one or two temporary exhibitions which cover a particular topic ;

- by means of its vivarium (an area, usually enclosed, for keeping and raising animals or plants), the Museum also exhibits a collection of little-known living animals – impressive ones, rare ones or ones threatened with extinction. As regards the latter, the Museum actively takes part in several scientific and reproduction programmes undertaken as part of endangered species conservation projects co-ordinated by EAZA (the European Association of Zoo and Aquaria) ;

- lastly, in recent years the Museum has set up and enlarged an Educational Department, which provides a large range of free activities, aimed both at families and at school groups.

La Société d’Encouragement du Musée

On 16 June 1830, an encouragement society was founded for the natural sciences by the members of the Museum’s Management Board. The society still exists today and its aim is to raise funds in order to allow the Museum to add to its collections.

La Galerie Bruno Renard

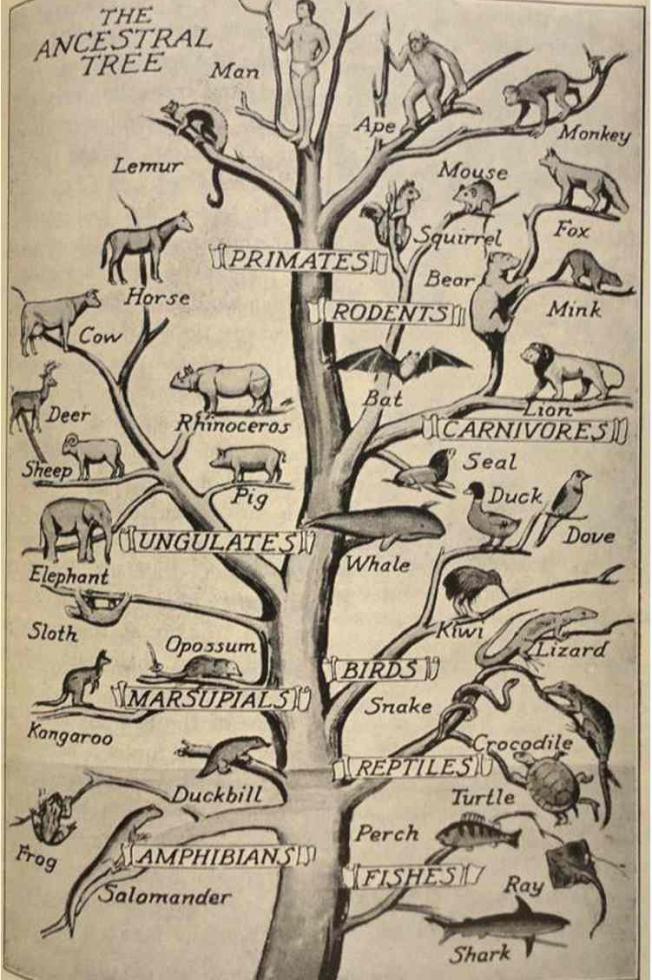

The need to classify and to organise things appears to be a characteristic which is specific to the human species. The classification of living things – a concept which dates back to Antiquity – has over time undergone profound changes.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, classification was schematised in the form of a ladder (or tree) in which organisms were categorised depending on what they had or on what they did not have, which appears to be from the least perfect (low) to the most perfect (high).

From the 18th century and up to the middle of the 20th century, the traditional classification scheme created by the Swede Carl Linnaeus, based on the most visible resemblances between species (the “Ducks of a feather flock together” idea) dominated. Yet, while this classification system can be easily used by the general public, it does not allow one to correctly assess links as regards how species are “related” to one another, and thus as regards evolutionary links between species.

This is why it was replaced in the second half of the 20th century by phylogenetic classification which enables us to understand the history of the evolution (phylogenetics) of species. This classification is based on the establishment of groups which include a common ancestor and all of that ancestor’s descendants. So the system is no longer only just based on physical resemblance but rather takes into account all inheritable characteristics, and employs approaches from the fields of compared anatomy, embryology, genetics, paleontological data, and so forth.

The Invertebrates Display Case

Bearing witness to the former exhibit design scheme of the Museum, the “Invertebrates” display case has been left unchanged to illustrate the traditional classification system created by Carl Linnaeus.

However, the exhibit design of the following display cases will be updated to reflect – as they are rearranged – the modern system of phylogenetic classification.

The Cabinet of Curiosities

The display case is evocative of the cabinet of a 19th-century naturalist, a time when the work done by scientists was mainly descriptive and handwritten. Using their documentation and their dissection and observation equipment (a magnifying glass, a microscope, etc.) they would observe, describe and classify fauna and flora, living things either native to Belgium or brought back from expeditions, more often than not preserved in alcohol or prepared by means of taxidermy. The fruit of their work generally gave rise to descriptive scientific works which were richly illustrated with sketches and drawings delicately done by hand.